The recent revision of the US tariff regime under former President Donald Trump marks a turning point in the dynamics of global trade, particularly for low- and middle-income exporting nations. This change is expected to create a favorable opportunity for several developing countries, with Bangladesh among the most prominent beneficiaries. With US reducing tariffs on Bangladeshi imports from a hefty 37% to 20%, a significant structural shift is unfolding for the country’s export economy – especially in labor-intensive sectors such as readymade garments (RMG), textiles, leather goods, jute products, and light manufacturing.

The core of Bangladesh’s export strength lies in its capacity to produce large volumes of low-value, labor-intensive products that cater to price-sensitive consumers in developed economies. These exports, though not strategically threatening to US industries, form an essential part of global retail value chains. The recent tariff cut not only improves Bangladesh’s price competitiveness but also strategically aligns the country with global sourcing trends in a post-COVID, post-China-dominant world.

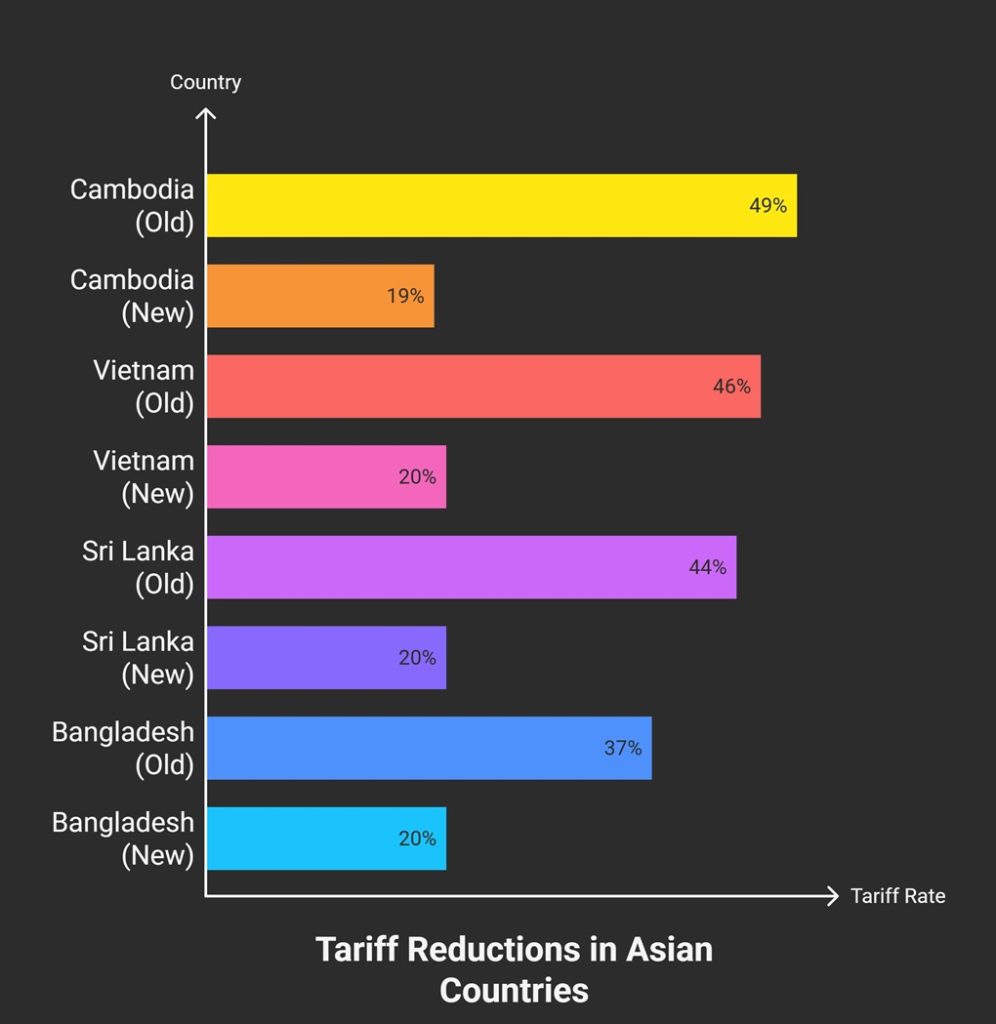

In the latest revised tariff schedule, Bangladesh joins a cohort of countries that have received significant tariff relief. Cambodia’s rate dropped from 49% to 19%, Vietnam’s from 46% to 20%, and Sri Lanka’s from 44% to 20%. While each of these adjustments improves market access, Bangladesh’s positioning is uniquely beneficial due to the scale and maturity of its garment sector. Bangladesh’s reduction from 37% to 20% represents not just cost relief, but a broad-based advantage in margin-sensitive industries where even single-digit tariff differences shape sourcing decisions.

US retailers and brands, struggling with inflationary pressures and rising input costs, are increasingly sensitive to import duties. For many of them, cost savings from lower tariffs directly translate to better pricing power in the American retail environment. As a result, sourcing from Bangladesh has instantly become more financially attractive. With few structural trade tensions or political hostilities between US and Bangladesh, there is no `business enemy’ status to interfere with trade flows-unlike countries such as China or even India, which face occasional diplomatic friction with Washington. This neutrality places Bangladesh in a strategically peaceful lane of commerce, free from the encumbrances of geopolitics.

Other countries that have seen large reductions-such as Lesotho (from 50% to 15%), Madagascar (47% to 15%), and Mauritius (40% to 15%)-lack the industrial base, labor pool, and export infrastructure that Bangladesh has meticulously built over decades. Bangladesh stands apart as a nation that is not just cost-effective but also production-ready. The garment sector, for example, has grown into the world’s second-largest exporter after China, supported by millions of skilled and semi-skilled workers, competitive wages, and improving compliance standards. This infrastructure enables buyers to place large, consistent orders with confidence, which many smaller economies with similar tariff reductions cannot yet accommodate.

In contrast, advanced economies like Switzerland have seen tariffs rise (from 31% to 39%), while Brunei, India, and Kazakhstan have experienced only marginal reductions or even slight increases. These changes signify a deliberate redirection of US tariff policy toward promoting trade with developing economies that pose no threat to US domestic industries, while simultaneously decoupling from major competitors and high-income economies that dominate strategic sectors. Bangladesh, in this equation, is a natural fit: large enough to matter, but not so large as to compete directly with US manufacturing.

What this means for Bangladesh is a medium- to long-term shift in the trajectory of export growth. With the right institutional and infrastructural support, the country can now gain deeper market penetration in US-not only in garments, but also in other low-cost, high-volume sectors.

Additionally, Bangladesh now has a stronger case to attract foreign investment in export-oriented manufacturing. US-based investors and brands may see an opportunity to deepen backward integration in Bangladesh by setting up or supporting facilities that produce raw materials, accessories, and packaging locally. As Bangladesh improves infrastructure, particularly in ports, highways, and industrial zones, it becomes more competitive not just in cost but also in delivery reliability—a factor as critical as price in the modern supply chain.

The perception of Bangladesh as a stable, low-risk exporter is also reinforced by this development. With countries like Iraq (39% to 35%), Libya (31% to 30%), and Serbia (37% to 35%) seeing only minor changes or even unfavorable treatment, Bangladesh’s clear jump indicates not only economic merit but a certain level of diplomatic favor. Despite some historical labor rights criticisms, the country has made visible strides in worker safety and compliance. These improvements now provide commercial returns through more favorable trade terms and reputational credibility.

Furthermore, Bangladesh’s large workforce and favorable demographics remain a long-term comparative advantage. With over 60% of the population under 35, there is a continuous supply of labor capable of feeding expanding export production. Despite automation in high-end manufacturing globally, the demand for labor-intensive sourcing remains strong in garments and similar sectors. Bangladesh, not being a political or economic threat to the West, fits naturally into this labor-demand equation.

The US tariff schedule also shows a clear pattern of rewarding least developed countries (LDCs) and lower-middle-income economies that are seen as benign trade partners. Côte d’Ivoire, Namibia, Botswana, and Zambia all now face uniform 15% tariffs—a notable recognition of their developmental stage. Bangladesh, while approaching graduation from LDC status, still enjoys similar tariff advantages, reinforcing its current competitive edge before it potentially loses other preferences upon LDC graduation. US seems to be pre-emptively smoothing the transition for Bangladesh, recognizing that continuity in trade access may aid economic and political stability in a vital part of South Asia.

Bangladesh’s government and private sector now face a crucial challenge: how to maximize the gains from this revised tariff schedule. First, there must be targeted investment in infrastructure upgrades—especially port capacity at Chittagong and Payra—and customs digitization to ensure quicker turnaround and lower transaction costs. Secondly, export financing facilities need to be strengthened, as small and medium exporters continue to face liquidity crunches that limit their ability to scale production for larger American orders.

Third, attention must be paid to product and market diversification. The over-reliance on RMG, while profitable, exposes the economy to shocks. With the new tariffs in place, sectors such as home textiles, furniture, sportswear, footwear, and even readymade food can be developed for US market with improved cost competitiveness. The creation of specialized export-processing zones (EPZs) dedicated to these sectors can further ease investor hesitancy and streamline exports.

Bangladesh must also focus on compliance and traceability to meet evolving buyer standards in ESG (environmental, social, governance) criteria. The positive shift in tariff does not guarantee orders unless brands are confident in ethical sourcing. Bangladesh’s recent progress in green factory certifications, environmental upgrades, and workplace reforms must continue and expand. Buyers increasingly reward suppliers who can provide transparent sourcing data, responsible labor practices, and minimal environmental footprints.

In the global context, this new tariff regime coincides with a broader trend of shifting supply chains. US and European firms are diversifying away from China due to trade wars, rising costs, and geopolitical tensions. Countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, and India are capitalizing on this. But they face bottlenecks in labor cost, capacity, or policy uncertainty. Bangladesh, in comparison, offers a combination of scale, stability, and now, tariff advantage. With Cambodia also benefitting from a drop (49% to 19%), there will be competition, but Bangladesh’s scale gives it an upper hand.

The road ahead is not without risks. The tariff reduction may not be permanent; future US administrations may revise trade preferences based on new geopolitical realities or domestic lobbying. Therefore, Bangladesh must use this current opportunity to invest in lasting competitiveness—raising productivity, enhancing logistics, and securing new markets. Trade diplomacy also needs to intensify. With Washington signaling goodwill through tariff reductions, Bangladesh should work to resume GSP negotiations and deepen bilateral commercial ties beyond garments.

The Trump-era revision of US import tariffs presents Bangladesh with a historic moment of commercial favorability. A shift from 37% to 20% redefines the margins for exporters and gives the country an edge not just in price, but in policy positioning. In a world where low-value exports are increasingly judged by geopolitical neutrality, efficiency, and ethical sourcing, Bangladesh stands out—with no business enemy, no strategic baggage, and a product profile perfectly suited for the American market. Now is the time to consolidate, diversify, and lead in a body by export communities to encounter the price-cut demand by buyers.