Bangladesh’s financial sector is lurching toward a crisis that could shake the very foundations of its economy. The latest Financial Stability Report (FSR) from Bangladesh Bank, released on Monday, reads less like a dry regulatory document and more like a grim tale of systemic weakness, capital erosion, and a mounting mountain of bad loans. Together, the findings paint a picture of banks and non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) teetering on the edge, while policymakers scramble to restore confidence.

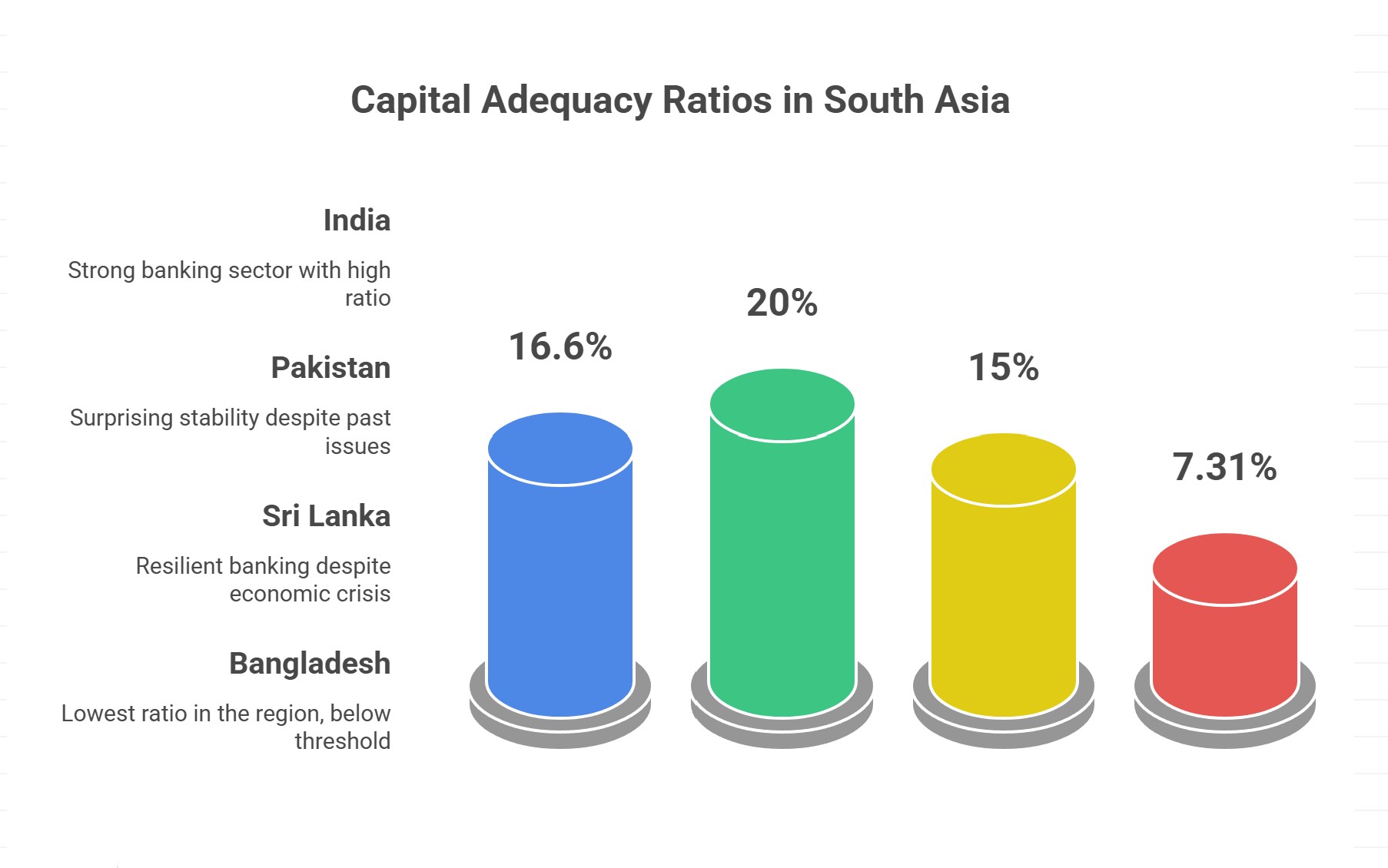

At the heart of the storm lies the capital adequacy ratio (CAR) — a measure of a bank’s capital relative to its risk. Globally, regulators demand a buffer of at least 10.5 percent under Basel III rules. In South Asia, most countries comfortably clear that bar: India’s banks, for instance, boast a sturdy 16.6 percent; Pakistan, often criticized for its instability, now reports over 20 percent; even crisis-stricken Sri Lanka manages more than 15 percent. But in Bangladesh, the ratio has plunged to just 7.31 percent by December 2024 — the lowest in the region, and well below the safety threshold.

For bankers and analysts, the figure is not just a number; it is an X-ray of a sector hollowed out by reckless lending, weak oversight, and poor governance. Several private and Sharia-compliant banks, riddled with governance failures, have dragged the entire system down. Behind their balance sheets lies a dangerous reality: too many risky loans, too little capital to absorb losses, and too few reforms to reverse the decline.

The rot becomes clearer when one looks at the scale of non-performing loans (NPLs). In just twelve months, the amount of bad loans in the banking sector has more than doubled, ballooning from Tk 211,391 crore in June 2024 to an eye-watering Tk 530,428 crore in June 2025. That means more than one in four taka lent by banks is now in default. The surge has been so steep that it dwarfs previous crises, threatening to choke liquidity and erode public trust. As one senior banker admitted privately, “This is no longer a problem of a few bad apples — it’s the whole orchard.”

But the banks are only half the story. The FSR’s spotlight on non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) reveals an equally disturbing picture. Out of 35 NBFIs currently operating in Bangladesh, only 14 could survive a severe shock. The rest — 21 in total — would see their capital wiped out in the event of simultaneous pressures: a spike in bad loans, defaults by their largest borrowers, crashing collateral values, a sudden fall in stock prices, currency depreciation, and rising interest rates. The scenario may sound extreme, but regulators describe it as a “rare but not impossible” event. For institutions already fragile, even a modest tremor could bring them down.

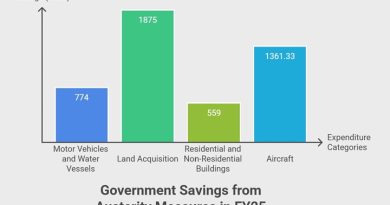

Bangladesh Bank’s acting spokesman, Mohammad Shahriar Siddiqui, did not sugarcoat the findings. He described the FSR as a “mirror for the financial sector”, one that forces policymakers, bankers, and the public to confront hard truths. It is not only about identifying the cracks in the system but also about prescribing cures. Among the recommendations: overhaul corporate governance, restructure bad loans, increase transparency in the foreign exchange market, strengthen cyber-security, and invest in digital infrastructure. Most importantly, the report stresses the need for regular stress tests so that institutions can prepare before the next wave of shocks arrives.

Yet, the question remains whether these measures will be enough — or whether they will come too late. Economists warn that without decisive action, the combination of weak capital, soaring NPLs, and fragile NBFIs could snowball into a full-blown financial earthquake. The implications are dire: businesses could struggle to access credit, depositors may lose faith in the system, and the government could be forced into costly bailouts. For a country aiming to graduate into middle-income status, such a crisis would be a devastating setback.

For now, the numbers tell a stark story: Bangladesh’s banks are the weakest in South Asia, its NBFIs are dangerously exposed, and its mountain of bad loans is rising faster than regulators can contain. The storm is no longer on the horizon — it is here. The only question is whether the country’s policymakers can act in time to prevent a financial collapse that could reverberate through every corner of the economy.