Dhaka, July 20 — Bangladesh’s industrial output has expanded significantly over the past decade, but the corresponding growth in employment has failed to materialise, raising concerns among economists about the country’s economic trajectory and inclusivity.

Between 2013 and 2024, the number of workers in industrial production units declined slightly — from 1.21 crore to 1.20 crore — despite strong growth in output. In 2025, the industrial sector contributed 34.81% to the country’s GDP, up from 27.55% in FY2010, with annual output growing by 10–20% in many years.

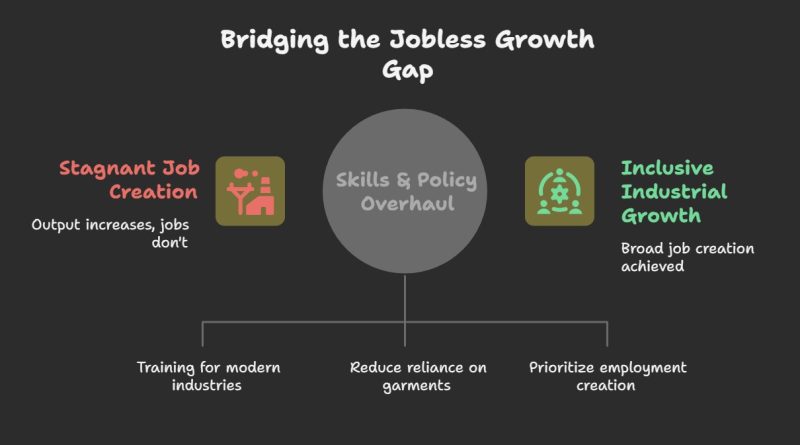

Economists describe this phenomenon as “jobless growth” — economic expansion that fails to generate adequate employment — and warn that it reflects deeper structural issues in the labour market, production technologies, and skills development systems.

“The declining trend in manufacturing jobs runs counter to expectations,” said Rizwanul Islam, former special adviser at the International Labour Organization (ILO). “It marks a reversal in the structural transformation of employment.”

Islam noted that while manufacturing employment has declined, agricultural employment has remained steady or even increased — a trend inconsistent with typical industrialising economies.

Automation and Skills Mismatch Drive the Gap

Experts point to the increasing use of automation and advanced technologies in large-scale manufacturing units as key reasons behind the disconnect between output and employment. These capital-intensive production models have enabled greater productivity without proportional increases in labour demand.

“Industrial growth is happening, but labour demand is lagging behind,” said Dr KAS Murshid, former Director General of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS).

Murshid, who led the Economic Strategy Redesign taskforce during the 2007–08 caretaker government, identified a growing mismatch between labour market demand and the available workforce. “We can no longer rely on a large population to drive employment. What’s needed is a technically skilled, semi-skilled workforce — and we are falling short,” he said.

He also cautioned that current skills training projects, often donor-funded and fragmented, are insufficient. “AI-driven technologies are redefining industrial needs, and Bangladesh is not yet prepared,” he added.

Skills Crisis and the Weakness of Policy Response

Economists argue that without a coordinated national approach to upskilling, the promise of inclusive industrial growth will remain unmet.

Khondaker Golam Moazzem, research director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), observed that much of the industrial growth over the past decade has come from large enterprises that have adopted technology-intensive production methods, often at the cost of labour demand.

“For example, Bangladesh now exports over $40 billion in garments with fewer workers than it did to earn $10 billion a decade ago,” he said. “This is a clear case of productivity-driven, not employment-driven, growth.”

He also pointed out that most new jobs are emerging in low-labour-intensity service sectors — warehousing, transport, insurance — rather than in manufacturing. Industrial expansion has not translated into broader job creation because of a lack of diversification and the dominance of readymade garments in exports, which now account for nearly 85% of export earnings.

Policy and Education Gaps Hold Back Labour Absorption

Prof Abu Eusuf, executive director of the think tank RAPID, highlighted the growing disconnect between academic institutions and industry needs. “We are producing graduates who are not job-ready, while foreign professionals are being hired for roles that should have gone to Bangladeshis,” he said.

He stressed the need for universities — particularly science and technology institutions — to focus on STEM and market-aligned curricula.

Eusuf also cautioned that tight monetary policy, though aimed at curbing inflation, is dampening private investment and, consequently, employment. “Political stability and a more favourable business climate are critical for reversing this trend,” he added.

Risks of Exclusion and De-industrialisation

Labour economist Nazmul Hossain Avi warned that the current trend signals early signs of “de-industrialisation” — where industrial employment stagnates or declines despite rising output — and “economic divergence,” where GDP growth benefits a smaller segment of the population.

“We urgently need to revisit the National Employment Policy (NEP) 2022,” he said. “It was poorly structured and lacked a robust implementation mechanism. Employment creation must become a cross-ministerial priority.”

Avi also emphasised that unless Bangladesh fosters a more diverse manufacturing base and scales up skills training, the economy will increasingly fail to generate “decent work.”

Former ILO adviser Rizwanul Islam added that the impact is particularly severe for women. “Manufacturing has historically offered large-scale employment for women, especially in garments. A contraction in these jobs disproportionately affects female workers,” he said.

“Low-productivity service jobs are not a substitute. They may sustain survival, but they do not lead to meaningful economic uplift,” he added.

Bottom line: As Bangladesh moves deeper into an era of technology-driven growth, economists warn that without urgent investment in skills development, policy reform, and job creation strategies, the country may face a growing employment deficit — despite impressive gains in output.