Liquidity is the bloodstream of any financial system. For banks, its availability determines not only operational stability but also the confidence of depositors and investors. For Islamic banks, however, liquidity management is uniquely complex. Unlike their conventional counterparts, they cannot rely on interest-bearing Treasury bills, bonds, or interbank repos. Their instruments must be fully Shariah-compliant, backed by real assets and structured on permissible contracts. The difference is not cosmetic—it is structural.

Bangladesh now hosts one of the world’s most vibrant Islamic banking systems. By mid-2025, Islamic banks accounted for around 25 per cent of deposits, 30 per cent of investments. Islami Bank Bangladesh PLC (IBBPLC) alone contributes roughly one-third of this segment, underscoring the industry’s systemic importance. When Islamic banks face liquidity pressure, the effects quickly extend across the wider financial system—affecting interbank rates, payment settlements, and, ultimately, depositors’ confidence.

Liquidity position: The structural imbalance

The foundation of liquidity management in Islamic banking differs fundamentally from that of conventional banks. While conventional banks may freely invest in interest-bearing Treasury bills, bonds, or repos, Islamic banks are bound by Shariah rules that prohibit any transaction based on interest (riba). As a result, their eligible high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) are limited mainly to a few government instruments such as the Bangladesh Government Islamic Investment Bond (BGIIB) and the Bangladesh Government Investment Sukuk (BGIS).

According to the Financial Stability Report (FSR) 2024 of Bangladesh Bank, the Investment-Deposit Ratio (IDR) of Islamic banks stood at 97.06 per cent in December 2024, surpassing the regulatory ceiling of 92 per cent. In contrast, the Loan-Deposit Ratio (LDR) of conventional banks remained comfortably within limits at 81.55 per cent against a ceiling of 87 per cent. The message is clear: Islamic banks are operating with far thinner liquidity cushions.

The difference arises largely from instrument availability. Conventional banks maintain a Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) of 13 per cent, holding risk-free government securities—T-bills and T-bonds—which carry 0 per cent risk weight under Basel III and yield stable returns. Islamic banks, in contrast, face a lower SLR of 5.5 per cent, reflecting the limited supply of eligible Shariah-compliant instruments. With most funds tied up in financing activities, their ability to absorb shocks or meet sudden withdrawals is constrained.

The liquidity instruments: Scope and limitation

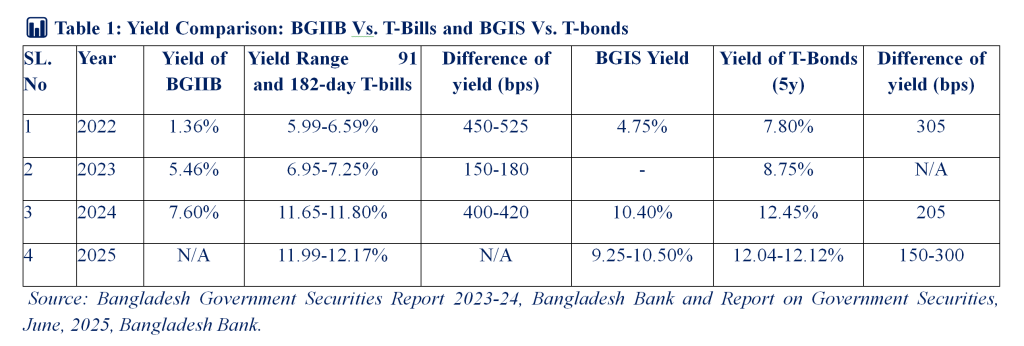

As mentioned, Bangladesh currently has two main Shariah-compliant liquidity tools: BGIIB and BGIS. The BGIIB, introduced in 2004, is structured on a pooled Mudaraba basis with tenors of 3 and 6 months where return depends on utilization of fund among the participating banks. The BGIS, launched in 2020, follows an Ijara (lease-based) structure and serves as the only tradeable Sukuk. While both qualify as SLR-eligible instruments, their combined outstanding volume—about Tk 35,000 crore as of June 2025—is marginal compared to more than Tk 7,00,000 crore in conventional government securities of T-bills and T-bonds. The gap is not only quantitative but also qualitative. The yield on Islamic instruments consistently trails that of comparable Treasury securities.

This persistent yield disadvantage—often 150 to 525 basis points—discourages active trading. Islamic banks, therefore, hold Sukuk and BGIIB largely for regulatory compliance rather than for liquidity management. Unlike conventional T-bonds, these instruments are rarely bought or sold in the secondary market. The result is a shallow Islamic money market, where liquidity is essentially locked within bank balance sheets.

In addition to above instruments, Islamic banks and Islamic windows/branches of conventional banks place their surplus funds with each other on Mudarabah principle, usually in the form of call, notice (14 days) and term deposits (1/3/6 months period) where rate of return is linked with Mudarabah Term Deposit Receipts (MTDR). However, the size is very negligible in terms of volume of Islamic Banks. Bangladesh Bank introduced Islamic Inter-bank Fund Market (IIFM) back in 2011 to address liquidity issues of Islamic banks, but its usage remains very limited which made it virtually ineffective.

Central Bank Support

Recognizing these limitations, Bangladesh Bank introduced several dedicated facilities. The Islamic Banks Liquidity Facility (IBLF) allows Islamic banks to obtain funds by placing Sukuk as collateral, effectively a Shariah-compliant equivalent of the repo. The Mudarabah Liquidity Support (MLS)scheme extends funding against receivables from government incentives—such as export subsidies and stimulus packages—based on profit-sharing principles. In FY2023-24, the central bank also offered Special Liquidity Support (SLS) against government subsidy claims on fertilizer imports and electricity tariff adjustments. Banks with large verified subsidy receivables could pledge them for short-term liquidity up to 90 days.

These measures helped avert a systemic liquidity crisis in late 2022–23, when deposit outflows and delayed reimbursements stressed several Islamic banks. Yet they remain stop-gap solutions. A sustainable Islamic liquidity ecosystem requires deep market instruments, regular issuance, and efficient trading—not reliance on central-bank windows.

Why this matters systemically

The asymmetry between Islamic and conventional banks has tangible consequences. Conventional banks can park surplus funds in government securities that bear no credit risk and attract zero capital charge. Islamic banks, deprived of equivalent instruments, must invest in private-sector financing that carries higher risk weights, thereby inflating their capital requirements.

This imbalance produces three cumulative effects:

1. Profit compression, because Islamic banks hold lower-yielding assets;

2. Reduced capital efficiency, since more risk-weighted assets consume capital buffers; and

3. Higher liquidity vulnerability, as limited HQLA restricts flexibility under stress.

When combined with episodic governance weaknesses and depositor sensitivity, these factors create a fragile equilibrium—where confidence, once shaken, takes time to rebuild.

Policy imperatives and the way forward

The strength of Bangladesh’s Islamic banking lies in its resilience and ethical foundation. Yet the next stage of growth demands structural reforms to ensure liquidity safety, competitive returns, and regulatory parity.

1. Utilization of BGIIB Fund Regular and Diversified Sukuk Issuance:

BGIIB fund may be utilized in bulk government imports (like consumer goods by TCB, Fertilizer by BCIC & BADC, Crude Oil by BPC) under Murabaha mode instead of limited use among participating banks. Bangladesh Bank and the Ministry of Finance should publish a quarterly Sukuk issuance calendar alongside conventional T-bill and T-bond auctions. Sukuk may be made available across tenors-from 3-month to 10-year maturities to build a benchmark yield curve. Short-term Sukuk will give Islamic banks a functional substitute for Treasury bills, helping them manage daily liquidity without violating Shariah. Moreover, the rate of rent of long-term sukuk to be made variable considering the market dynamics to make them attractive among the investors.

2. Establishment of an Islamic Interbank Market:

An effective Islamic Interbank Fund Market (IIFM) should be developed using standardized Wakalah and Mudarabah contracts, enabling short-term placements among Islamic banks and Islamic banking windows. This will reduce dependency on Bangladesh Bank’s emergency facilities and promote market-based liquidity flows. Bangladesh Bank can also introduce Islamic SDF (Standing Deposit Facility) to park surplus fund of Islamic banks in a Shari’ah compliant manner.

3. Deepening Secondary Market and Investor base:

Designating selected banks as primary dealers for Sukuk will create two-way quotes and continuous trading. Widening Sukuk investment to insurance companies, pension funds, and mutual funds will expand market depth. The more actively Sukuk trade, the more efficiently Islamic banks can adjust liquidity positions.

4. Strengthening Liquidity Risk Governance:

Each Islamic bank should conduct quarterly stress tests under varying withdrawal and market scenarios, disclose Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR)separately, and integrate Shariah oversight into its Asset-Liability Committee (ALCO) deliberations. Bangladesh Bank can issue separate Liquidity Risk Management Guidelines tailored for Islamic institutions, aligned with IFSB-12 principles.

5. Building Depositor Confidence and Governance Discipline:

Liquidity resilience ultimately depends on public trust. Transparency in financial reporting, consistent profit distribution policies, and visible Shariah compliance will rebuild confidence that was partially eroded in recent years. A centralized Shariah Supervisory Board at Bangladesh Bank, as proposed, could ensure uniform interpretation and enforcement across institutions.

6. Collaboration and Capacity Building:

Developing an Islamic liquidity market requires coordination among regulators, banks, and scholars. Joint research initiatives with BIBM and universities can standardize contract documentation and risk management practices. Training ALM professionals in Islamic liquidity concepts will close the current skills gap.

A forward-looking reflection

Liquidity management is more than a regulatory requirement; it is a measure of stewardship. For Islamic banks, it embodies the principle of amanah—the trust between depositors, investors, and the society. Strengthening this trust demands more than compliance; it requires creativity, discipline, and foresight.

Bangladesh’s Islamic banking industry has already proven its vitality through four decades of steady growth. The challenge now is to equip it with instruments and governance structures with moral aspirations. By expanding the Sukuk market, institutionalizing an interbank platform, and embedding transparency in liquidity management, Islamic banks can evolve from reactive stability to proactive resilience. The time has come to move from dependence to self-reliance—building a Shariah-compliant liquidity system that is not only sound in faith but also sophisticated in function.

[The author is an Executive Vice President and Head of Financial Affairs Wing, Islami Bank Bangladesh PLC. The views expressed in the paper are the author’s own and not necessarily the organization he represents. He can be reached at raihan.accaglobal@gmail.com]